Git Rebasing to Resolve Conflicts

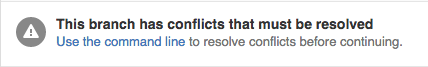

Four years ago when I first started contributing to open-source projects git was new to me. I quickly grasped committing files and pushing to a remote repository. However, I was absolutely terrified of seeing the message saying my code couldn’t be merged.

Project maintainers would review my code and then ask me to rebase so they could merge. Wiping away the sweat I would go to work rebasing. Many times I would fail and completely mess up my work. It was often easier to redo the work than to figure out how to rebase properly and get a clean set of commits pushed.

Over time I learned some tricks and I now rebase with ease. I’m sharing these tips hoping they help eliminate another hurdle new contributors face. After reading this post remember to practice rebasing, be patient and don’t be afraid to ask for help. Project maintainers should be understanding and willing to point you in the right direction.

In this post I will cover a “standard” rebase that will resolve merge conflict issues. Another common type of rebase is an interactive rebase to squash commits. I will cover this in a future post.

Rebasing to resolve merge conflicts

These tips assume you have created a feature branch off of the master branch for a project. Additionally,

origin refers to your fork while upstream refers to the original/upstream project. Both can (should)

be configured as remotes for your git repository. If you’re not familiar with this concept see “Configuring upstreams”

below for more information.

First, ensure you have a clean state. That means you have either committed, stashed, or reverted any untracked

changes. When you run git status you should see nothing to commit, working directory clean.

Next, switch to the master branch and pull upstream changes by running git pull upstream master.

Switch back to your feature branch and initiate the rebase by running git rebase master --preserve-merges.

If all is well you will see Successfully rebased and updated refs/heads/<branch>. If you see

an error you will need to resolve the conflicts, commit, and

continue the rebase.

Before examining how to resolve conflicts I want to revisit the rebase command for a moment. What does

--preserve-merges do? There are lots of details but one main reason I settled upon using

this flag is that a merge preserving rebase considers a smaller set of commits for replay. Over time

I had the most success (least nasty conflicts) by using this flag. This is certainly not required to

do a normal rebase but I recommend trying it. If you’re interested in the details this SO article titled

What exactly does Git’s “rebase –preserve-merges” do (and why?)

has a very in-depth explanation.

To resolve any conflicts that occur during a rebase start by running git status to see what

conflicts are present. Conflicting files will appear under unmerged paths:

$ git status

rebase in progress; onto 519c739

You are currently rebasing branch 'changes' on '519c739'.

(fix conflicts and then run "git rebase --continue")

(use "git rebase --skip" to skip this patch)

(use "git rebase --abort" to check out the original branch)

Unmerged paths:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: conflicting-file

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

By examining the conflicting-file contents we see a set of weird characters:

$ cat conflicting-file

foo

<<<<<<< HEAD

qux

quux

=======

bar

baz

>>>>>>> f78d8ae... <commit message>

The changes between <<<<<<< HEAD and ======= represent changes made in upstream master since your branch

was checked out. Changes between ======= and >>>>>>> f78d8ae... <commit message> represent

changes in your branch. Git does not know which order these changes should go in. I cannot

give you perfect advice on how to resolve every conflict. You may only want the old changes,

the new changes, or both. Over time you will gain a better understanding for how to resolve this

problem. In this case we want both changes but need to adjust ordering slightly. Remove the markers

and make the ‘code’ look like something sensible:

foo

bar

baz

qux

quux

Commit this file as you normally would (git add <files>; git commit -m 'commit message') and then run

git rebase --continue. This will continue replaying commits until another conflict is encountered

or all commits have been replayed. Sometimes there

are many conflicts that must be resolved but hopefully the rebase is smooth.

Once complete, you will need

to force push your feature branch to the origin (your fork) to update the merge request. Do this by

adding a -f flag to your push - git push origin <branch> -f. Always examine the merge request

after this operation to ensure the commits and changes are what you expect.

I hope this helps next time you have to rebase. Please send me a tweet if you have questions. I’m happy to help a new contributor overcome these hurdles.

Configuring upstreams

As mentioned earlier in this post, I recommend configuring your local git repository with both origin and upstream remotes. This allows easily merging upstream changes into your fork.

Start by forking the project you want to contribute to. Do this in the web UI.

Then, copy the clone URL of your fork. Clone the repository on your workstation with git clone <url>. This action

will not only clone the repository but it will automatically configure your fork as the origin remote. Now

we can add the upstream remote. First change into the repository you just cloned and run

git remote add upstream <upstream-url>.

At this point you have two remotes configured. If you run git pull upstream master you will pull upstream

changes into your local repository. You can then update your fork by running git push origin master.

Unfortunately I don’t have comments enabled on my blog yet. If you have comments, please send them to @drewblessing on Twitter.